Image from www.elephantjournal.com

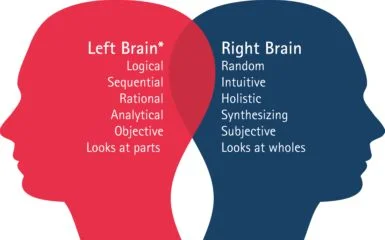

According to Peter Docker, ‘Starting With Why’ is only effective if you put it into action ‘right to left’ thinking.

Docker explains more in the Simon Sinek podcast, "Normally we operate with ‘left to right’ thinking. Drawing on past experience to dictate our future. A project manager will follow their past experience then apply logic to the present to gain a predictable future that can be measured.

“However drawing on a pattern such as ‘we’ve always done it this way’ is limiting. Many times we have all heard that things are done in an organisation in a certain way. Yet no-one seems to know why it must be done this way and why it is so entrenched. This is also limiting.

“You might do a good job, but it is unlikely you will achieve anything truly new.

“Anything that is overly linked to the past isn’t always good. It is a little backward in thinking. Now I like history and I think it is interesting and we can learn plenty from it. Yet it is always surprising to see the same patterns repeating themselves from Ancient Rome to WW2. And this is due to a human need to conform whilst not risking anything or appearing to make some kind of mistake.”

So relying only on left to right thinking can restrict progress. This approach will not create breakthrough products. Doing something new that provides genuine new value is hard to measure quite simply as it is new, so a different style of leadership is needed to get new results. So it is possible you will not have any kind of system that will be able to replicate success using proven models. Because you are trying new things, there is no model to follow.

Right to left thinking is different - you start in the future where it is you would like to reach and what it is you want to accomplish.

Docker uses a brilliant example in the famous speech made by John F. Kennedy in relation to NASA’s moon landing mission. The vision was to put a man on the moon by the end of the decade (the end of the 1960’s). He was clever by placing a time limit on it and he then shared it with the world. Crucially, he believed it was possible.

This point, Docker explains is really important. Having a goal, making this goal public and therefore making yourself accountable for it is important. It raises the confidence of others in your intentions and raises the bar, makes the whole thing more exciting, inclusive and galvanising. When you possess the individual confidence to believe that it is possible this creates support, trust and an environment for people in your team to achieve and believe that they can do it.

If your goal is audacious and has significance, then there is not going to be a preordained model to follow in a left to right fashion. So creativity is important in order to move ahead with a path that will lead to achieving the goal. The fact that one doesn’t absolutely know how to do it at the beginning is often what prevents people away from trying it at all.

So you may not know how you are going to do it but by believing and setting a very clear ambition, then standing from this place and looking back down the path is right to left thinking. And believing it is possible is vital.

Docker explains that you need to visualise yourself in the future as if you have already accomplished it and feel like you have - people will sense this, not just with what you say but with how you are saying it. This in itself is positive visualisation. It is about seeing yourself succeeding, despite not having a clear idea of how you are going to do it at the start. The reality is that people who seemingly achieve big things do just that. They act despite not knowing the answers.

I think this is different to simply setting a goal. How?

Docker explains, “It is different due to the mindset - your goal may be to reach the top of the mountain - it is the difference between standing at the bottom of the mountain and looking up and standing at the top and looking down. Docker recommends rehearsing the sense of exhilaration and the feeling of achievement - at the top, you get a different perspective as you are viscerally connected with it - there is no doubt you can do it.”

What Kennedy did with his public declaration of putting a man on the moon before the end of the decade, (Armstrong made his ‘Giant Leap’ in 1969) is called declared thinking.

With declared thinking there is no doubt that you have achieved it - you may not yet know how but you will be able to work it out and you will achieve it.

For another example, Usain Bolt, in the Olympic final of the 100 metres, uses declared thinking. He acts as though he has already won it. In fact, his behaviour before and after the race is not vastly different - he doesn't look surprised to have won. Because he has already envisioned winning.

“Before the race, in his mind he'd already run it he was already connected to winning the race - it's not arrogant - just the way he was being (behaving) he had won it - he had already connected with the feeling of crossing that line, a total commitment to what is going to happen .”

Highly effective leaders can envision a future that does not yet exist and secondly they are articulate in how they communicate that belief. Not only that, they are effective at getting others to see the same thing.

According to Docker, this starts with defining ‘the why’. You may not know how or what but with the why you know the direction you are going and your inner core and beliefs, your energy and actions will align.

When this is coupled with the right to left thinking it begins to take effect. Where you declare the direction you are going - this commitment creates the culture and the environment for others to step up with you to make that happen. With a simple goal you are aiming for it, but there is an inherent implication that this may not happen. But with right to left thinking, you have already made it in your mind but you haven't just worked out the detail yet.

Adaptive Leadership

After the ‘why’ has been defined, the ‘how’ must ensue. Adaptive leadership is about the ‘how’. Ronald Heifetz is a leadership expert. He is the King Hussein bin Talal Senior Lecturer in Public Leadership, Founding Director of the Center for Public Leadership[1] at the John F. Kennedy School of Government, Harvard University, and co-founder of Cambridge Leadership Associates.[2] Heifetz’s work revealed that when people talk about problems and challenges, we tend to group them together despite them being distinct from one another. But he found that there are both technical challenges and adaptive challenges.

Technical challenges are those that present themselves to us that are similar to past challenges. Therefore we have some reference to the past that we can apply in the present because there is in place some kind of ‘best practice’ model for those in authority to apply. This enables us to operate within a comfortable zone of operation by applying knowledge and proven models of success. Indeed, the leaders that are generally applauded in the traditional sense are those that are able to effectively and quickly solve this kind of problem.

These technical challenges are relatively easy to define, direct or delegate. As long as the leader has had some experience in his field, he has become an expert. And experts are applauded by people. In fact, we are applauding experts within this book, and rightly so. However, experts have not always been the ones breaking boundaries.

In contrast, adaptive challenges are new and there is no set model to deploy. In our rapidly changing world, where new paradigms are being defined and old ones are being destroyed, increasingly we must become willing to solve adaptive challenges.

This means that the technical leader will not be able to solve these kinds of problems alone.

Docker explained that Heifetz defined the economic crisis of 2008 as an adaptive challenge. Whilst the recession had occurred before, the banking crisis that precipitated it had not happened before, so there was no set technical model to fix the problem.

Adaptive challenges require a collaborative model where people need to work through the problem. Traditional leaders struggle with this. They find this hard as they are used to dictating solutions based on technical models. They may find this a huge threat to their self. This kind of outlook will not help us solve the challenges of the future.

Docker, in his podcast, explains that John F. Kennedy was an adaptive leader. With his statement ‘putting a man on the moon by the end of the decade and then permitting an environment for the right people to solve the problem, he laid out a right to left vision and there was no sense it may not be attained.

With an adaptive challenge, the leader has to empower others to come up with the solution by learning a way through a problem together. This represents a very different kind of approach to leadership v the traditional model. So it changes from direction and delegation to creating the environment to empower teams to learn their way through the problem. This is how it links back to right-left thinking, it requires creativity and it must link back to the ‘why’.

So What?

So how often do we applied a left-brain ‘technical’ model to try to solve a problem or achieve a goal? Worth thinking about. The solution is not always found by simply following a well-trodden path.